Q&A with Harley Bassman. MBS, Fixed Income Volatility.

- Interview with Harley Bassman, Managing Partner at Simplify Asset Management, and the author of The Convexity Maven. Tian and Harley discuss his new-issue MBS Strategy (MTBA), opportunities within fixed income markets, and more.

- Links to our recent MBS write-ups: MBS ETFs: Why now & how | A better way to own duration

- Read more of Harley's content on his website: The Convexity Maven

- Other useful links: Intro to Mortgage TBA

Tian: [00:00:03] Hello everyone! Today, I'm joined by Harley Bassman, managing partner at Simplify Asset Management and the author of Convexity Maven — in my opinion, one of the best publicly available resources to learn about fixed income volatility. And so, I'm really glad we have this opportunity to connect and kind of get to pick your brain. So yeah, Harley, welcome.

Harley: [00:00:26] Thank you. Good morning. I will also say that I'm not dressed in my usual attire, seeing as I got X million time zones here; I kind of woken up early. But whatever, you guys get to see me in my natural state.

Tian: [00:00:39] Perfect. So, obviously, what led up to this particular interview was that I actually reached out to you guys when I saw the news on MTBA, the ETF that you just launched on mortgage-backed securities. So, I think it's really interesting. We live in a world of so many ETFs. There's basically like an ETF for everything going. So it's very rare that we see a product where you just get instant resonance going like, "Yes, this just solves all these problems. It just makes sense." And so, the last time that we had one of these reactions was actually in response to one of your earlier product, PFIX, back in '21, where we were just scrambling, looking for ways to get kind of swaption upside as a non-fixed income specialist. So, I feel like you have a really great track record. Just hitting it out of the park with these products. I'm really looking forward to getting to pick your brains on the kind of thought process on what leads to these products and obviously how you're thinking about managing these today. So, I guess, the first question is, why do you think this opportunity exists today in MBS market? Why now?

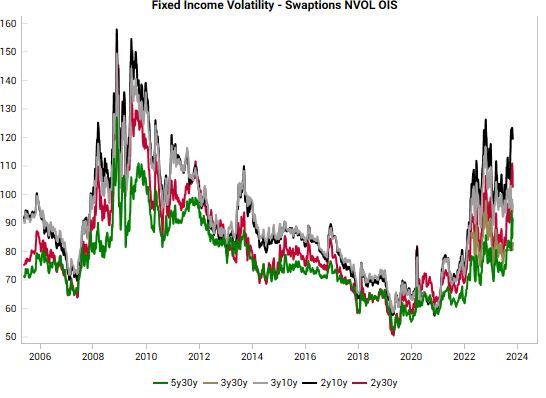

Harley: [00:01:51] Let me give a little background here. So, I'm 35 years corporate Wall Street, 26 years at Merrill Lynch where I ran mortgage trading, derivative trading, option trading. I'm in that realm of convexity, optionality. Remember, there are three kinds of risks you can get: duration, credit, convexity. Those are your three buttons. That's it. I'm talking bonds, not equities. Duration, credit, convexity. They tend to go together where you'll see the curve steepen, vols go up, spreads widen — all the same kind of thing over there. What's anomalous now is duration sucks because the curve is inverted. So, you're paying money to get duration. Credit? Look at IG. It's trading at what, 71 now, which is kind of ballpark average forever in front of the Fed saying, "Hey guys, we're going to slam on the brakes until we stop this train and get rid of inflation." So, why do you want to take credit risk at average [levels]. You take credit risk at 90 on IG; The MOVE Index is at 120. That's not the wrong price, but it's a high price. And the old rule is, you buy at 80, you sell at 120. That never actually worked because when the MOVE was under 80, the market was very calm, very peaceful, and no one ever thought it was going to happen. So, they didn't buy vol. And at 120, they're so scared they're hiding under their desk crying for mommy. So it never works out. But, that is the idea. If you look at a mortgage security, it's basically a buy right. That's how you can model it up.

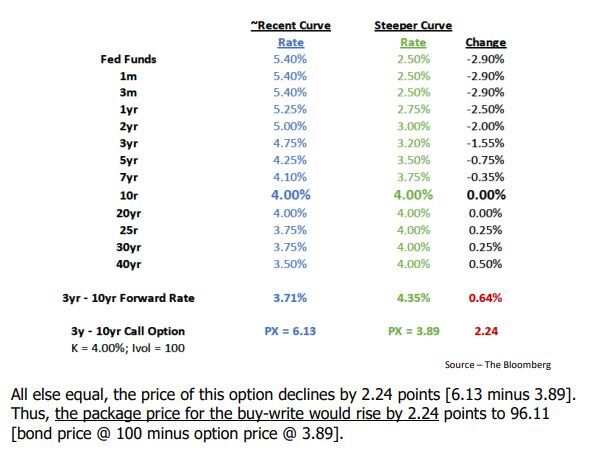

Harley: [00:03:24] And you can say, "I'm buying a ten-year bond at par at 100. I'm selling a three-year expiry option, not three-month, three-year option. Big, meaty, fat option struck at 105." That's kind of what a mortgage looks like. It's not a buy right; it just acts like one where your upside is limited and your downside is more. That's the definition of convexity. Convexity just means it's not a linear process. So if you go and buy, something, you make a bet, you do anything where for equal changes you make a dollar or lose a dollar — zero convexity. Linear. You make two, lose one — positive convexity. Lose three, make two — negatively convex. The reason why we hired all these PhD quants 20, 30 years ago on Wall Street was we had to sort of all of a sudden get involved in optionality, path dependency. And we need to model up this thing to figure out if I have a security that yields, let's say, 5%, and it's a linear return called a treasury, although they're positively convex, we'll ignore that small detail. If I have a security that is up two, down one, well, that's a better bond, right? How do you adjust for that in the world? You get a lower yield, right? If you're going to get better performance, you got to pay for it, and you pay for it with yield. So the question is, should it be 3.90, 3.75, 3.50?

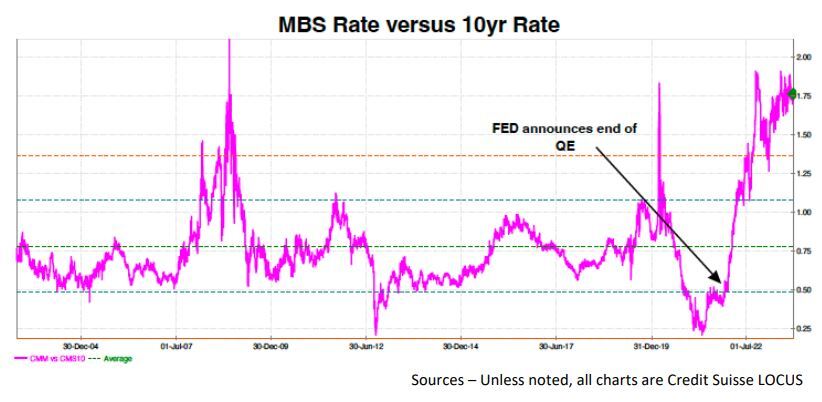

Harley: [00:05:01] You got to go find out what that convexity option is worth. Similarly, a negatively convex bet — lose three, make two — well, you're going to get you're going to have to get paid more for that. Once again, the currency is yield. So should it be 4.10, 4.20, 4.50? Traditionally. Historically, you've seen mortgages, new issue bonds trading near 100, near par trade about three-quarters of a point, 75 basis points over the ten-year. And you can go to my website, convexitymaven.com . I have the charts everywhere. I always talk about this. We are at 175 right now.

This is like crazy, off the charts nuts. It's as high as it was during the Covid crash in March 2020 and in '08-'09 during the GFC. Yet, I don't see a debacle now. Lots of reasons why it's happening; don't care. I'm just saying it's at 175, and it will go back to 75 in due course. The two reasons why it's there, I'll tell you, one is vols are high. You're selling a big option now. Vols are high. The option is worth more, and you're selling it.

Two is the yield curve. That's trickier. I'd recommend you go to my last two commentaries on my site, where I go through this in kind of detail.

Little geeky, but if you're interested in this stuff, you should go look at it because mortgages are an incredible yield curve bet. But I suspect we'll talk about that later on. So, what happened is, I'm minding my own business.

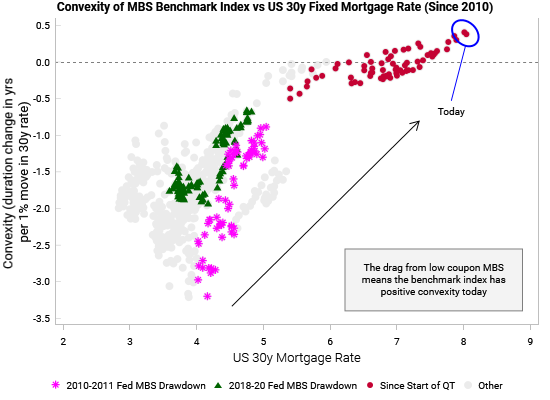

Harley: [00:06:43] Oh, one more thing. I'm at Simplify now. I was retired, kind of done. And Simplify, they are guys from Pimco who spun off and started this company, and what they did was this. They recognized that the SEC made a rule change about five years ago where ETFs could buy derivatives, futures, options, swaps. All those things couldn't do that before. They could only buy cash instruments. They can now trade derivatives. I'm a deriv guy, man, I got a lot of clever ideas about how to go and take professional, institutional products that trade over the counter and put them into an ETF. The first one was PFIX, that was the obvious trade, which was trading at 1%. Man, I mean, they can only go up, and vols are very low. And now I'm a mortgage guy, and I'm looking and saying, "Well, 175 over the curve? That's the wrong price." Now. The big boys, Gundlach, Gross, and all the other guys out there are all screaming mortgages are the wrong price. They’re way too cheap, buy them. Here's the small detail. This is the important part. When you go and buy a mortgage product that's index-based, you're buying a 3% bond. Fannie threes because 72% of all 30-year securities are between 2% and 3.5%. Everyone got on the train and refinanced from 2020 to 2022, and these bonds called Fannie threes are trading at 79 to 81. These are terrible bonds. And they're not the bonds trading at 175. It's the new bonds, Fannie sixes, trading at 99.

Harley: [00:08:40] Those are the ones trading at the wide spread. So we created, we launched a few days ago a new product where it only buys those specific Fannie six or depending upon the market, these bonds near par. The big fat juicy mortgage bonds. Why? No one's done this in the past. I don't know, because it's so goddamn obvious. But we're doing it, and it's, I will say it's the best bond ticket out there. Now, if you think rates are going a lot higher. Okay. Fed’s going to 7%. We're going to massive inflation. Don't buy this. Don't buy any bond. Just go to cash. Okay. If you think we're going to go into a double hard landing where rates are going to drop 200 basis points in a month. Once again, don't buy this. It's a covered call. Why would you want to go and sell a call on the upside. Both those scenarios, they're possible, but not in my general view of the world. I think we're higher for longer. I think the Fed's done. Maybe one more hike. They're not taking rates down for at least six months, maybe longer. They're going to wait until they either get inflation at a two handle or unemployment at 4.2% / 4.5%. And that's going to take time to cook. So, doing a trade where you're doing a buy right and picking up this extra income in a world that's going to be kind of range bound. That's what you do.

Tian: [00:10:10] Yeah. Perfect. I think what drew us to your product was precisely, as you mentioned, we looked at the popular ETFs, MBB, the Vanguard ones, where if you actually look at the index, the entire MBS index is positive convexity.

So that just tells you everything. How to your point how 70% of it the coupon is so low. And so that's what started us on this journey. And drew us to your product.

Harley: [00:10:34] One thing though. The Fannie three has positive convexity. For two reasons. One, a fixed income product by definition has positive convexity, so a treasury has positive convexity. A 30 year a lot more than a two year. It's not like an option. It's very small but it does have some curve to it. What's happened is you have this positive convexity in a fixed income security and a fanny three trading at $80 price. And you're short an option that's negatively convex. So that option is trading for pennies. It has no impact on this thing. And which is, if you got mortgage prices to go up a little bit, that option would start to kick in and that bond would turn negatively convex. But here's the issue. If you're buying a fanny three you're buying duration. That thing is a duration longer than the ten year okay. You're going to go buy that bond if you want. If you're buying that kind of bond, that kind of duration, you're buying it because you think bad things are going to happen and you want to make a profit when rates go down. Yet you're selling this way, way out of the money call for pennies. That's foolish. You don't sell options for pennies, okay? You sell options, you sell big meaty options where you get paid. Because remember, when you're short an option, your gain is limited. Your loss is unlimited. Your long an option. Vice versa. You don't go during a buy right where you sell a way, way 300 basis point out of the money call. That's just kind of nutty.

Tian: [00:12:06] Do you think there are any structural reasons why this opportunity also exists, just in terms of the players in the market? Because I think my understanding is kind of the 2 to 5 year point is where a lot of the MBS desk and derivative guys are quite active. But now that, as you say, yields are higher, that, my understanding is for most of the issuance, a lot of these natural suppliers, but this, this point in the vol curve, they've kind of stepped away a bit. So you may be ending up with a little bit of a demand supply imbalance. That means that longer dated fixed income vol is higher. And it's screaming out for people to kind of step in. But the natural supply might have gone away. I mean, is that a fair way to look at it?

Harley: [00:12:44] I'm sure somewhere on your website you discussed Formosa Bonds and what they do. So I'm not going to go through it here. The answer is no. Vols are not high because for most of the issuances is down, vols are high because we're moving. I mean, we're generally for options, short date options for sure. You will see the implied vol trade 8 to 12% over the realized vol. That's why you have like a Two Sigma out there. And they go out there and they sell one month options every single day. And at 4:00 they delta hedge and they skim off that 8 to 12% premium. It's an insurance premium is what it is. And it exists for non-linearity, kurtosis and other things out there. But it exists. And as long as you slice that trade right, you'll win. People get hurt because they usually sell too much volatility, too much convexity. And then when things go crazy they get stopped out. So when you sell convexity you got to go size it right. You've seen the back end of the curve. Massive volatility I mean the bond contracts are moving a point change every day now, that's why vols are high because the market's moving that much. It's not because of Formosa okay. Mortgages are wide for two reasons. One, high vols. Two, the yield curve. Do you want me to go into why the yield curve matters? I'm not sure I want to do that. It's kind of dirty business. Go look at the Center Cut.

Harley: [00:14:14] I released it on November 1st. Look at pages seven, eight, and nine. That'll explain why it happens. But it’s because the yield curve. But what you also have happening is this. You've gotten rid -- who was the biggest buyer of mortgages once upon a time, Fannie, Freddie. These were basically government backed hedge funds where they own a trillion mortgage bonds and hedge them out. After they blew up, they were told, you can't do that anymore. And so they no longer buy mortgages. They just do what their job is supposed to be doing, which is guaranteeing and wrapping mortgage bonds and creating liquidity. That was their public policy purpose. It was not to go and be a hedge fund to go and pay Franklin Raines a lot of money, which is a public policy. Bad, by the way. With Fannie and Freddie gone, the hedge funds went with them because what we knew once upon a time was that was that, if I knew Fannie or Freddie would buy 25 OAS. So a measure of option adjusted spread where you could hedge out the bonds. If we got to 35. Well, I know they're coming in, so I'd front run them and buy mortgages. If they got to 15, I know they're going to sell, so I'd front run them. So basically hedge funds were front running Fannie and Freddie, who operated in a very kind of programmatic manner. Well, with them gone, there's no one to go keep things in line. So they're gone also. So you're left with banks and foreign governments and retail.

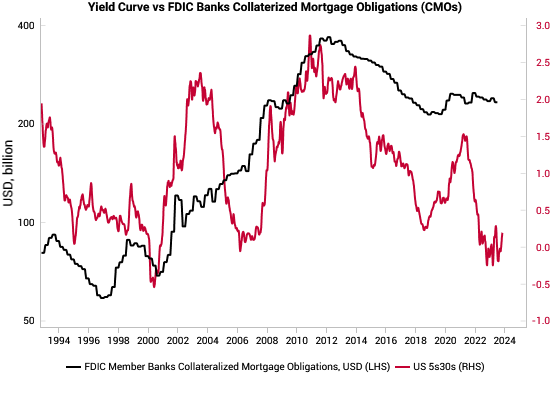

Harley: [00:15:42] The banks aren't buying it now because they basically got caught with their pants down as rates went up. If you look at what happened. As rates went up, the Treasury portfolios of people actually shortened. It shortened because treasuries are positively convex. They get shorter when rates go up and longer when rates go down. So they still got killed, obviously. Look at the various banks on the West Coast that got taken out. But nonetheless the Treasury portfolio were kind of okay. The mortgage stuff whipped out there. I mean, there are Fannie twos-- a trillion and a half Fannie twos. Can you believe that? They're trading like $75 price $74. I mean, that's nuts. They bought these bonds at par, and they went from being a four year to being a 12 year. They didn't hedge it. And so they're kind of cooked. The other problem you have is this. What we used to do on Wall Street. What we still do, but it's not as much is this. We take the mortgage cow. And no one wants to buy a cow. You want to go out and get a nice steak, right? And we chop it to pieces and we'd sell some hoofs to him, some noses to him, some filet to him. And after we added them all up, it was called a CMO-- collateralized mortgage obligation. So the obligation is based on the mortgage which is collateral behind it. And we would chop these bonds up and sell them.

Harley: [00:17:14] And the parts would be more than the whole. We make money on that. What would drive it is that banks would want a five year on-in piece of paper. And the insurance groups would want the 20 year on-out piece of paper because they think this long liability of life insurance policies and with a steep curve, if I had a 5% bond, but twos were trading at like three, I could strip off a lot of these front end cash flows and sell them at 3% or 3.5% to a bank, and that would leave these back ends. If I have a 5% security and I sell half of it at three and a half, I got the back end at six and a half. And then they love that thing. So the whole thing worked. When the curve inverted, everything's upside down. Now, I can't do an arbitrage anymore because the front end bonds are trading at a higher rate than the ten year. So the CMO machine is cooked right now.

And those two things, banks are full in the name, and CMOs are problematic because of the curve. So that's the reason why. I mean, if you look at the OAS of mortgages, they're actually-- they're cheap, but they're not nuts. Once you adjust for the yield curve and for implied vol mortgages are I won't say fair, but they're okay. But the thing is, you are selling a high vol and you are making a bet on a steeper curve. So what's wrong with that?

Tian: [00:18:34] Yeah. Well, awesome. Thanks for that. Something else I noticed reading your piece on your website was you mentioned about the financing rate and how potentially there's an extra edge from doing these TBAs instead of holding the cash bonds. Again, I'm curious if you'd be willing to talk a little bit about why sometimes that gives you a bit of extra edge.

Harley: [00:18:56] Oh, God, we're really going geeky, aren't we? Okay. In general, retail civilians can't buy mortgage bonds for lots of reasons. One of them is they really don't want to do it. If you buy a legit mortgage bond, a pool number, a CUSIP into your account, you're going to get every month money. And that money will be some interest and some principal. Because remember, a mortgage is a self-amortizing instrument that goes away in 30 years. So, every month a level pay, you're paying 2000 a month for your mortgage. Some of that is principal. So, you're getting that back into your account which means you have to reinvest that money. So, if you have $1,000 today invested in a mortgage bond, you might only have $850-900 a year from now. Well, that could be okay. But maybe you want to reinvest it because you have an allocation. You have to go, and constantly every month go and reinvest that money. You're paying a bid offer on that. It's transactional. It's a headache. You don't want to do that. Number two is there's a tax problem. When you get your 1099 in late February, early March, it'll have all your interest payments from the mortgage bond. What's going to happen, though, is you're going to get a 1099 supplemental two months later, because that principal that came back, if you bought the bond at 95. And you're getting back 100 every month.

Harley: [00:20:21] A little bit of 100. That's a five-point profit. Or you bought at 105, 5 point loss. That's a capital gain [or loss], and the bank or broker has to go and report that to you on your tax forms. Well, you're not going to—I mean, you could have already filed your taxes when the supplemental 1099 comes in. You're not going to like that one bit. It's just dirty. So that's why you really only see real cash, mortgage bonds trading with institutions, just because it's a pain. Most mortgage bond trading—90%—is in the TBA, to-be-announced market. It's basically mortgage futures. And the thing about mortgage futures is, you bought the instrument, you have the economics, but the cash doesn't change hands till a month later. Well, what if I buy the Fannie 6 November bonds, which we did, and then after a few weeks, we go and we sell the November and buy the December. We roll it, and the price spread between those two will be the mathematical economics of the coupon, the price, repayments, and the funding rate. And that will go and give you your total return. What happens sometimes is that roll spread, you could take that number. So let's just say it's a 2/32nd spread, a 6 cent spread between November and December. You can go to Bloomberg, watch those two things in. You can punch in a dollar price, you know…

Harley: [00:21:55] what the coupon is, you put in a prepay, which you can kind of guess at, and it'll back into the implied funding rate, the implied repo rate. And now, Ginnie sixes are trading at three ticks for a funding rate of 4.88. Well, if I'm implicitly borrowing at 4.88 and I keep my cash in treasury bills at 4.50, I'm earning an extra 38 bps. That's a very popular strategy. And if you go look at, like—some of the big tickers—but some of the big REITs, you know who they are. Go look at their statement, and they will have somewhere in line three "roll income." That's what it's from. Because they're rolling. They don't own cash bonds. They're rolling them every month. And they're also vastly more liquid. I mean, mortgages are the most liquid thing on the planet because it's the biggest market out there. I mean, you have a trillion and a half Fannie two’s. How big is the Treasury issue? 80 billion? I mean, these issues are much bigger than the single issue treasuries. It's much easier to buy 100 million Fannie sixes than to buy a hundred million cash 10 years. Hard to believe. So in our new strategy-- instead of buying cash Fannie sixes, I buy TBAs and roll them.

Harley: [00:23:21] And by doing that, you never get a prepayment; you never have a tax problem. I just give you money every—every month. Now it's taxable money, okay, no free lunch here. But I basically embed that reinvestment in the roll. So if I have 1,000,000 Fannie sixies in Nov, I roll it to a million Fannie sixes in Dec, and the prepayment is embedded into the mathematical calculation. So this is just a vastly superior way. And it's the only way, as I can tell, for retail civilians to buy mortgage bonds. I will say I have owned mortgage bonds in the past in my personal account, and I was running the mortgage department, so we used to buy these things if they were interesting. It's just dirty business, man. You don't want to do it. And truth be told, even institutions—like good-sized institutions—should buy this ETF because it saves them the trouble of reinvestment. It saves them the offer. It saves them a lot of stuff over there. And if we're charging 15 basis points for that, I can make that back up in the roll. So I mean, look, if you're Pimco or Blackrock, you're going to buy pools, and you're that, but if you're, a two, three, five billion dolalr fund, or, a manager with SMA money, you definitely buy my product. It's a slam dunk.

Tian: [00:24:46] So the mechanism you describe sounds obviously very similar to the kind of cash-futures bond basis trade that's been making a lot of headlines recently. I was just curious if you had any comments, because obviously, the Fed has come out talking a lot about the worries, but obviously, most of the practitioners seem quite relaxed in terms of, cheapest to deliver of the futures.

Harley: [00:25:07] My product is mathematically identical to buying two of the products that we have, where you buy the two-year futures contract, we do 5 to 1, we buy the futures contract. I don't owe you any money. I buy T-bills with the cash you've given me. And I roll those contracts every—every quarter on the exchange. And once again, that has an implied repo. Also, the same nonsense goes on there. And so. That's very easy. The basis trade is different because I'm not hedging my product. I'm an unlevered one-for-one, dollar-for-dollar product. You give me $1,000, I will go and buy $1,000 of TBA mortgage bonds. The basis trade is you buy or sell treasuries, and you buy or sell the other side futures. And for various reasons, those things we know on the last day of the month, this goes into that. It's kind of like you buy gold in London and sell it in New York. If that price spread is bigger than the cost to buy the boat and ship it over there, you do it; you ship it; you deliver it in. That's what futures are. They're a forward agreement for me to deliver to you or receive from you something. Well, in this case, bonds. These guys go out there and they say, well, I got this here, I got that there; I can borrow here. And I got a profit. And they're doing this trade, and it's basically free money because you're guaranteed to deliver it and it collapses.

Harley: [00:26:42] No, it's not quite free money. There are two reasons why. One, if you go to the CME website you can go—or Bloomberg on the DLD screen—you can see the ten-year futures contract. You have about ten bonds you could deliver in there. You don't know which one you're going to get. Now usually, you will get what's called the CTD, the cheapest to deliver. That's the bond that'll go in there. The thing is, depending upon rates, the curve, and other things, bond number one all of a sudden does not become CTD, might become bond number five. Well, if you've bought the Treasury and sold the future, or vice versa, I guess. Let's say you're long the future; you may not get the collapse. You may be short bond one but receive bond five, and now you've got a spread trade on which you can't get out of. That's problem number one. That's not that big of a deal now for reasons that don't matter. The bigger reason is this. Let's just say all hell breaks loose. You see Treasury futures explode higher; cash bonds are going to follow, but maybe not as fast because everyone's, like, out of their minds looking for mommy. And so you're going to see this. Things diverge. It'll come back in two days, but on day one, it doesn't. Well. You're short. You're some big hedge fund, and you're short to Goldman Sachs, and then you're long on the other side of futures to the CME. Each side is going to demand you pony up money.

Harley: [00:28:20] Well, if it goes like this, you're going to owe more money on that than you'll get from Goldman. And then you've got a problem. So what you have is a mark-to-market issue, very short-term. But nonetheless, you get margin called. You don't have the money; they close you out. And that's the problem we have here is you're kind of short a disaster option in the basis. It's short-term. But if you, when 3:00 rolls around and the boards close, the CME is calling you saying, "Give me the money, man," or "We're closing you out." If you don't give them the money, like, you've got a problem. That's why the Fed had to come in and just calm the market down. Is this a good or bad thing? Well, I'll say that if a hedge fund goes bankrupt on this, they should go bankrupt and be gone, like Long Term Capital did. That's a good thing. They are providing liquidity to the Treasury by being buyers of treasuries. I think they own 400-500 billion of these things now, which is policy good. But I mean, they are short this kind of disaster option. I will bet, I know all the guys who are doing this stuff, they're pretty good at this. They're very big firms and they know what the risks are. So it's probably okay. Could a small firm go under? Yeah it could, it could.

Tian: [00:29:37] I see. I was just drawn to the concept. Obviously, I'm not in the space. I'm just drawn to it because there were hints of similar ideas you have in your piece about the fact we have lots of different coupons now, which I think means there might be more optionality in terms of delivering in-- into the futures. So I was just curious if you thought about taking advantage of this time and launching strategies on, on this kind of concept as well?

Harley: [00:30:01] Well, I mean, the TBAs, I mean, the reason why they call it TBA—to be announced—is if I buy the November TBA contract, come delivery date, which is the 3rd week of November, some dealer—Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America—is going to deliver to me $1 million of mortgage bonds. I'm not sure which bonds they're going to give me. Could be good ones. Could be bad ones. Actually, I can assure you, they'll be the worst bonds. That's what we used to do. We used to go and just give the worst possible bonds if people wanted delivery. Who owns the ultimate-- the really worst bonds in the world? The Fed. The Street would just love to go. We give the Fed all the worst bonds out there. I mean, they were still full faith and credit Fannie Threes. But they were bad bonds. Bad because they were more negatively convex for a variety of reasons. What reasons would they be? They'd be high loan balance. They'd be high WAC. They'd be California versus Iowa. People are more mobile in California. They'll prepay faster. So you see things like that happening. So we would go through bonds and look at each individual pool and figure out where it is. And we'd price that out. And we'd give the worst bonds to the TBA guy. I will never take a bond in. This is why I don't want to buy specified pools because I, I mean, I kind of know what I would get, but they're less liquid and they're a pain in the neck. So who buys—who takes delivery? Places that can't take TBA and can't take leverage.

Tian: [00:31:39] A last question from me on the MBS side. So obviously, this is designed for, as you say, the civilians. I'm just curious if, say, you were one of the lucky individuals who went and locked in your mortgages when rates were very low. In a way, if you went and bought the low coupon mortgage back, you've closed that implicit short you have, right? So for those guys with their original mortgage, how should they be thinking about it? Presumably, it still probably makes sense for them to invest in your product. But I'm just curious how you would frame that.

Harley: [00:32:11] I mean, actually, in Denmark, you could actually buy your mortgage back and take the profit. The Danish mortgage bonds are a separate entity that is very sexy on Wall Street, that a few guys trade them and everyone else has no idea what's going on. You can only get a 30-year mortgage that can be prepaid with no cost in two places on the planet: one's the US, one's Denmark. That's it. Everywhere else is adjustable-rate mortgage bonds. Theoretically, if you borrowed money for your mortgage at 3% but didn't buy a mortgage, you just kept the cash, so you took out a line of credit. And then you held and you didn’t invest it, and you waited until now. And you bought mortgage bonds. That would be, I guess, an arbitrage of sorts. I think that's a little—I think that's too clever by half, that notion.

Tian: [00:33:07] Yeah. Awesome. I also want to pick your brain a little bit on PFIX because obviously, that's been fantastic timing and really done its job. I'm just kind of curious how you're thinking about it today because, my impression is, obviously a lot of it has come from the directional move. And again, I'm not an expert in the fixed income vol space, but one of the appeals of the product originally was that you got a lot of the Vega exposure on the way up. But obviously, now, given the speed of the moves, one concern would be the Vega's dropping off very quickly in your swaptions. Have you thought about maybe tweaking—doing some of those things to maintain the appeal of the product?

Harley: [00:33:47] The answer is no, because when the vol term surface plays out, what we own is still much lower in vol, easily 20% cheaper than the three-year point. So the vol surface kind of goes up and then goes down. So we're out here with the part where it's positive carry on the vol—is the whole term surface too high or let's just say high—not too high. High? Yes. Do I love owning Vega up here? I don't love it. I mean, I loved it when it was trading at 60. When it's trading at like 90, it's like, yeah, not so much, but, you are still long convexity-- and how I phrase it is this, two years ago the trade was a no-brainer. Slam dunk. I mean rates can't go any lower. And the MOVE was at 60. It was a slam dunk. No brainer. Now it is a brainer. You got to think about things. Would I buy PFIX outright? No. Because we're at 5%, I mean you can go to six. Yeah sure. But I mean they can go—they can go to four also. I mean, it's not—I mean it's not as uni-directional and vols aren't crazy cheap, however. What you can use PFIX for is a hedge.

Harley: [00:34:59] It's always been a hedge, in my view. You don't buy PFIX because you were bearish on rates. You buy it because you're bullish and you might be wrong. So what you're supposed to do is buy duration. And then go and own PFIX as the hedge against it because it has positive convexity to it. As a matter of fact, the killer trade is you buy my new mortgage strategy and you buy PFIX. That's—that's—that's the killer. Because then you're basically short a three-year option, which is the hump of the vol surface. You're buying a seven-year option which is much lower down, and you're taking out this Vega on this slope. And then both those trades are a massive curve steepener. I mean, the hedgy trade is to buy PFIX and MTBA? That's a trade. If you guys are going to do it be my guest. But don't come back to me crying. But I mean if you—if you were a model geek, that would be the trade to do because you're taking out the—the Vega's and you're taking out the durations and you're left with the curve trade. I'm actually—I'm going to guess that’s a positive carry curve trade.

Tian: [00:36:19] So you brought up something very interesting, which is the term structure of the vol surface, right? Which obviously to a civilian is quite hard to see for fixed income. But I'm curious if you ever thought about a product specifically to monetize that, because obviously there's a lot of VIX curve, obviously that's at the front end. But now, to your point, in terms of 1y10y versus 10y10y, are those like very good carry kind of opportunities as well?

Harley: [00:36:44] The way you get to these are two ways. One's a variance swap, which—I mean those are—I'm not going to tell you what these things are, but you can't put them in an ETF. The bid-offer is too wide. To do an ETF, I need to go with something that trades somewhat actively and somewhat liquid. Shockingly, a seven-year option on the 20-year rate is rather liquid. The bond market is vastly bigger than the equity market and much more liquid, so you'd think they'd be tough, but it actually isn't. A hundred million is gentleman size, so I can get in and out of those things because remember, I have my market maker, my AP, the approved something, and they can go and basically buy and sell from me, the issuer every day at 4:00. And I will then give them shares or take back shares at the NAV. So I have to transact near the NAV every day or when required at like 3:30-3:45. So I'm somewhere near the 4:00 close. For stock that's easy. You just put in an order to go buy or sell on the close. They actually have a mechanism to go and trade at the close. That's why we charge four basis points for some of these mega funds because there's zero slippage. I have slippage, but in general, it's not that bad. A variance swap would be a gigantic spread between there.

Harley: [00:38:10] It just would not be—the bid-offer would absorb all the economics. Same thing with forward vol swaps. Another great idea, but the bid-offer is too wide. I mean, it's a trade. It's a trade that belongs not in the ETF but in a structured note, an ETN, something like that. But can I get retail civilians to go buy a structured note on variance swaps? Maybe, but I'm not going to try that. I got bigger fish to fry. This ETF we have here, it's incredible. I just really don't understand why someone didn't think of this before. Because it's just so bloody obvious. But here it is. And it's going to trade like water, man. Because the underlying asset trades like water. I got Jane Street as the market maker. I mean does it get better than that. Zero credit risk. So to repeat. If you go, the trade you're supposed to do is sell the legacy mortgage index ETFs. You know what they are. And you buy my product, my strategy, dollar for dollar. You will pick up 200 basis points in coupon. You'll go from a 3.75 to a 6. You'll pick up maybe 80 in yield to maturity, which is very suspect on a mortgage bond because you just don't know what [in audible] are going to be. But theoretically you're picking up 80 to the index. Your duration is going to go from a 7-ish to a 4- ish. That's the key thing--you're given duration.

Harley: [00:39:46] You're going from the ten-year point to the five-year point. Nothing wrong with that. But just be aware that if you're really bullish on rates, if you do the swap dollar for dollar from the index to mine, then you've got to go and get back the duration. What I would do—there are two ways you can do it. One is our levered two-year ETF. I love that trade. But then you have a monster curve trade on because you're long in twos and mortgages are long the front end. So again, I think that's the trade to do. I mean, you hear Druckenmiller? He said he's basically bet the ranch on the front end. If you're a little more squeamish about this, you don't want to take that kind of risk. You want to be closer to the index because, well, people are measured by the index, buy TLT. I don't like that thing in general, but by TLT, you gain the 20-year spot duration. Do not buy the 30-year; do not buy zeros. Those are bad because then you're getting way out. You're on the wrong part of the curve. So don't do that. Definitely don't buy zeros out there. That's a mess. So buy the 20-year spot rate. You don't buy the forward rate, but the spot rate, that’s TLT.

Tian: [00:40:55] Yeah. Well, awesome. No, I really appreciate you humoring me and really earnestly answering. I've just genuinely had a lot of these vol questions to ask. So something I thought I would end on is, I've been a long-time reader of the Convexity Maven. Like I said, I feel like I've learned enough to be dangerous, but I always wanted to ask you questions on how to think about structural, Asian exotic supply, all these elements that I don't really have a good handle on. But something else that I think makes your report stand out is you often remind people about life and balance. So, I really love that you have this phrase you end most of the reports with about turning off the CrackBerry (Did I just date myself?). So I'm just curious, like, do you still use a BlackBerry?

Harley: [00:41:38] No-no. But I never used the good app where you could put like the company server onto your personal phone. And they said, "Don't worry, it's separate." It's like, no, it's not, man. It's all spyware. I always had two phones, one for work and one for personal use. And I still advise you to do that now. Don't trust these guys, man. It's all spyware.

Tian: [00:42:02] Awesome. Well, yeah. Harley, thank you so much. Like I said, I think, and just to clarify, we have no financial affiliation. We just noticed the product. Thought it was—the blink was just yes. This is a no-brainer kind of thing. So, thank you for doing this.

Harley: [00:42:16] So my website, convexitymaven.com, I got stuff going back to 2006. Basically, it's my library. I put a lot of interesting things in what's called the Maven's Classroom, where I've picked out commentaries that are really kind of theoretical about a concept as opposed to transactional as a trade. And if you want to get—and I publish every six, eight weeks, whenever I'm in the mood—if you want to be on my list, just send me an email. It's on my website. You can send me one. I'll add you to my list, and remember: Sizing is more important than entry level. Don't get cute. If you have a good idea and you like it, just go and put half your money in today. You're not going to time this thing, I can promise you that. Do the right size. The right size means you invest enough so that if you're right, you feel it, and if you're wrong, you're not stopped out. That's the plan.

Tian: [00:43:14] Perfect. Thank you so much.